Rocky Mountain High

I’ve been to desert, ocean, city and swamp. I’ve swum with sharks and sea lions, encountered deadly snakes and wrangled with disingenuous locals. I’ve climbed a bridge, visited temples and photographed skyscrapers. I’ve downed delicious tropical juices and devoured mounds of Chicken Rice. What’s a traveler to do next? How about climbing a mountain?

Mount Kinabalu in Malaysian Borneo is thee tallest mountain between the Himalayas and Papua New Guinea. At 4,095 meters (13,435 feet), Kinabalu can’t compete with the world’s great peaks. It’s not even half as tall as the five highest peaks on the planet. Kinabalu doesn’t even rank in the top 100. It’s a runt in a land of giants. But I’m a hiker, not a climber, and 13,435 feet is a noble challenge.

Mount Kinabalu Obscured by Clouds

(As Seen From Kinabalu National Park Headquarters)

"Selamat Mendaki" (Happy Mountaineering)

The trek takes two full days. I would stay in a hostel in Kinabalu National Park, at 1,564 meters (about 6,000 feet), then wake early for a day of hiking from Timpohon Gate to the resthouse at Laban Rata, a distance of six kilometers and 5,000 vertical feet. I would then spend the night in a hut at 11,000 feet, waking up at 2 a.m. to tackle the summit, a climb of 2.7 kilometers and an additional 2,500 feet of elevation. Numbers are all well and good, but don’t tell the whole story.

Everyone who climbs Mount Kinabalu must hire a guide. My guide was Julius, a deceptively reserved local who has spent his entire life within ten kilometers of Mount Kinabalu. He started working as a porter when he was 14. Now, at 28, he doesn’t know how many times he’s climbed to the summit. He does, however, estimate that he could make the 18-kilometer round-trip in about five hours. Life all the porters and guides I encountered on the mountain, Julius was strong as an ox and modest as a wallflower.

Julius was an excellent guide and climbing partner, never pushing me to go beyond my own pace, and happy to point out flora that I would otherwise have missed, like the carnivorous pitcher plants that trap their prey in a cup of sticky syrup. He was also good for conversation, delivering a string of out-of-left-field questions like “Do you know Chuck Norris?,” “Do you like women with big breasts?” and “Do you believe in black magic?” These moments of absurdity help me immensely and I thank Julius for his offhand take on the world. He was also my unofficial photographer, though he could use a lesson in composition and the importance of a level horizon.

Julius, Master of the Mountain

I’ve done my share of hiking, and wasn’t concerned about the climb itself. Other travelers said I’d be sore in the days to come, but that seemed par for the course. What I discovered soon after passing through Timpohon Gate, however, is that Mount Kinabalu is more climb than hike. There’s nothing subtle about the trail; it is rocky, steep and treacherous. Well maintained, yes, but challenging. About 20 meters out 8.7 kilometers is on level ground. The rest is incline, over rocks and roots, up steps, around boulders and across rock faces. The steps are tall, consistently up to my knee and sometimes up to my thigh. Even with the walking stick, I often struggled to find my footing and had to pay attention to every step.

The Summit Trail...

...It's a Walk in the Park

Within the first hour of the climb I started to feel fatigue. But Julius gently urged me forward, telling me, “You are a very strong man,” and I soon found a comfortable pace. We covered the six kilometers to Laban Rata in four hours and forty-five minutes, arriving at 1:30 in the afternoon. I was the fourth climber of the day to make it to the camp, and I entered the empty resthouse exhausted and happy. Still, I was unable to eat, unable to do anything but rest my head on a table and wish for unconsciousness. I checked in at registration and dragged myself another ten minutes up the trail to my hut, where I found a comfortable bunk and two warm blankets.

Panar Laban Hut

I awoke three hours later feeling rested and alert, and returned to the resthouse for a meal. What had been an empty hall in the early afternoon was now crammed to the rafters with climbers. There was tempered excitement in the air. Everyone in the room had climbed up the mountain; we were equals in this endeavor whether the climb had taken four hours or fourteen (the average is about six hours). We were a collection of weary faces and slumped postures, but we were now some of the highest people in Southeast Asia.

I retired to my bunk at 7:30 an settled in for a few hours of sleep. Julius woke me at 2 a.m. After snatching a quick cup of weak coffee at the resthouse, I gathered my supplies (headlamp, gloves, hat, camera, energy snacks, multiple layers of clothing) and set out to conquer the summit.

Julius and I had hiked through rainforest most of the previous day, and had spent the night in an alpine zone of stunted trees and sparse shrubbery. Now we would cross the timberline and hike cross a great slopes of bare granite. The air was thin, but at least the terrain was fairly even.

We set out at 2:40 and within a few minutes passed a young woman vomiting by the side of the trail, a visceral reminder of the situation. Anyone can climb Mount Kinabalu – it doesn’t require mountaineering skills and can be accomplished in a sturdy pair of walking shoes. The climb is, however, very strenuous and without a moderate level of physical fitness you will suffer. And there’s the unpredictability of altitude sickness –even the strongest of athletes can be hobbled by elevation.

I was aware of the altitude, and decided to take my time. If it took five hours to hike 2.7 kilometers, so be it. As I trudged up the mountain, my progress slowing as I gained more elevation, I thought of every National Geographic special I’d seen about Everest, recalling how climbers would take one step, then rest, another step and another rest. And here I was crossing 12,000 feet, taking a few steps at a time, and resting. I was walking slow, slower than I’d ever walked in my life, slower than a tourist on Seventh Avenue or rush hour traffic on Santa Monica Boulevard.

I pushed on, following the thick white rope that guides climbers up the naked rock to the summit. The full moon had passed a night or two earlier, and I was able to turn off my headlamp and hike by moonlight. Jagged peaks were outlined against the starry sky. Perhaps it was the exhaustion, or the realization that willpower was propelling me closer and closer to my goal. Perhaps it was the elevation. Whatever it was, I couldn’t think about reaching the top without experiencing an upswell of emotion, tears of joy threatening to erupt at any moment. But I kept my emotions in check and set my sights on the only thing that mattered: the summit.

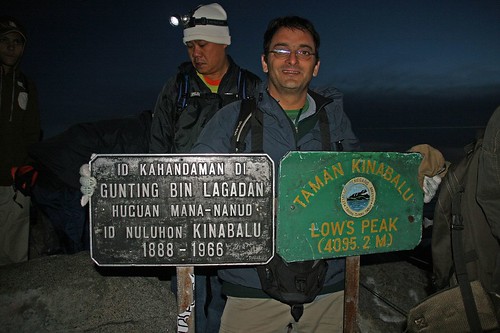

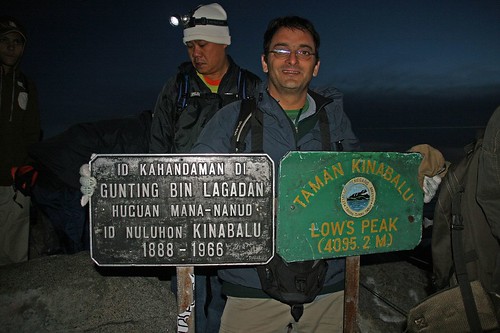

Low's Peak (4,095 Meters)

My legs felt great, but I was acutely aware of my lungs and my heart rate. Passing 13,000 feet, I’d push myself 10 or 20 feet and have to stop, gasp for a few breaths while my heart thudded in my chest. It took me an hour to cover the last 500 meters. I covered the final 100 meters at a slow crawl, using hands and feet to clear the jumble of boulders below the summit.

Meanwhile, Julius was like a kid at the playground, jogging up and down the slope behind me and bouncing up and down for warmth. I should have hated him, but was inspired by his enthusiasm. Even after 14 years and countless ascents, he displayed an impish glee at being at the top of the mountain. I’m sure Julius earns a paltry salary for his efforts; he deserves much, much more.

There’s an old saying that the journey is the reward, not the destination. I reached the summit, asked an older Japanese man to take a few pictures of me and was quickly ready to start climbing down. The sun was about to break the horizon, and there were dozens of climbers clamoring for space on the narrow summit. Also, I felt a sudden surge of nausea and didn’t want to vomit on the expanse of Southeast Asia that lay below me.

The Summit

With the rising sun illuminating the slopes, I took my time on the descent, photographing the peaks that were only outlines an hour before. A cottony layer of cloud covered the land, perhaps a thousand feet below me. I realized that no birds were singing, no frogs croaking, that plant life was stunted and wispy, clinging to the crevices in the rock. I was tired, so tired, but still in awe of the scenery, appreciating every moment I had earned with hard work and perseverance. I was reminded of my love for the Australian Outback and the American Southwest, for the harsh spaces where only the hardiest of species survive. Beaches and forests are great, but for me there’s real beauty in the barren. I wonder where that comes from?

Moon Over Kinabalu

View From the Top

South Peak

Sunrise Over Kinabalu

Two hours later I was back at Laban Rata, eating a breakfast of ramen noodles and ready to complete this adventure. But Kinabalu National Park had one more surprise in store for me. The park is in a rainforest. I had been lucky the previous day and climbed without encountering one raindrop. On the descent, however, the rain never let up. It never poured, just a steady mist and drizzle that increased the difficulty of the trek. All those steep slopes, the rocks and roots were now wet and slippery.

On the hike down, we encountered the next day’s climbers making the ascent. I urged them on with words of encouragement, telling them the summit was worth the effort. Around kilometer two an elderly Australian man asked me if the climb got any easier. I should have said it was a piece of cake, but told him the truth, that no, it really doesn’t get any easier, that it’s a slog from start to finish, both going up and coming down. He seemed put off by my answer, but asked me if I’d do it again. Without hesitation, I said “Yes.”

I surprised myself with this quick response. Mount Kinabalu was the toughest climb of my life, a challenge for mind, body and spirit. I loved every terrible minute.

Mission Accomplished!

Mount Kinabalu in Malaysian Borneo is thee tallest mountain between the Himalayas and Papua New Guinea. At 4,095 meters (13,435 feet), Kinabalu can’t compete with the world’s great peaks. It’s not even half as tall as the five highest peaks on the planet. Kinabalu doesn’t even rank in the top 100. It’s a runt in a land of giants. But I’m a hiker, not a climber, and 13,435 feet is a noble challenge.

(As Seen From Kinabalu National Park Headquarters)

The trek takes two full days. I would stay in a hostel in Kinabalu National Park, at 1,564 meters (about 6,000 feet), then wake early for a day of hiking from Timpohon Gate to the resthouse at Laban Rata, a distance of six kilometers and 5,000 vertical feet. I would then spend the night in a hut at 11,000 feet, waking up at 2 a.m. to tackle the summit, a climb of 2.7 kilometers and an additional 2,500 feet of elevation. Numbers are all well and good, but don’t tell the whole story.

Everyone who climbs Mount Kinabalu must hire a guide. My guide was Julius, a deceptively reserved local who has spent his entire life within ten kilometers of Mount Kinabalu. He started working as a porter when he was 14. Now, at 28, he doesn’t know how many times he’s climbed to the summit. He does, however, estimate that he could make the 18-kilometer round-trip in about five hours. Life all the porters and guides I encountered on the mountain, Julius was strong as an ox and modest as a wallflower.

Julius was an excellent guide and climbing partner, never pushing me to go beyond my own pace, and happy to point out flora that I would otherwise have missed, like the carnivorous pitcher plants that trap their prey in a cup of sticky syrup. He was also good for conversation, delivering a string of out-of-left-field questions like “Do you know Chuck Norris?,” “Do you like women with big breasts?” and “Do you believe in black magic?” These moments of absurdity help me immensely and I thank Julius for his offhand take on the world. He was also my unofficial photographer, though he could use a lesson in composition and the importance of a level horizon.

I’ve done my share of hiking, and wasn’t concerned about the climb itself. Other travelers said I’d be sore in the days to come, but that seemed par for the course. What I discovered soon after passing through Timpohon Gate, however, is that Mount Kinabalu is more climb than hike. There’s nothing subtle about the trail; it is rocky, steep and treacherous. Well maintained, yes, but challenging. About 20 meters out 8.7 kilometers is on level ground. The rest is incline, over rocks and roots, up steps, around boulders and across rock faces. The steps are tall, consistently up to my knee and sometimes up to my thigh. Even with the walking stick, I often struggled to find my footing and had to pay attention to every step.

Within the first hour of the climb I started to feel fatigue. But Julius gently urged me forward, telling me, “You are a very strong man,” and I soon found a comfortable pace. We covered the six kilometers to Laban Rata in four hours and forty-five minutes, arriving at 1:30 in the afternoon. I was the fourth climber of the day to make it to the camp, and I entered the empty resthouse exhausted and happy. Still, I was unable to eat, unable to do anything but rest my head on a table and wish for unconsciousness. I checked in at registration and dragged myself another ten minutes up the trail to my hut, where I found a comfortable bunk and two warm blankets.

I awoke three hours later feeling rested and alert, and returned to the resthouse for a meal. What had been an empty hall in the early afternoon was now crammed to the rafters with climbers. There was tempered excitement in the air. Everyone in the room had climbed up the mountain; we were equals in this endeavor whether the climb had taken four hours or fourteen (the average is about six hours). We were a collection of weary faces and slumped postures, but we were now some of the highest people in Southeast Asia.

I retired to my bunk at 7:30 an settled in for a few hours of sleep. Julius woke me at 2 a.m. After snatching a quick cup of weak coffee at the resthouse, I gathered my supplies (headlamp, gloves, hat, camera, energy snacks, multiple layers of clothing) and set out to conquer the summit.

Julius and I had hiked through rainforest most of the previous day, and had spent the night in an alpine zone of stunted trees and sparse shrubbery. Now we would cross the timberline and hike cross a great slopes of bare granite. The air was thin, but at least the terrain was fairly even.

We set out at 2:40 and within a few minutes passed a young woman vomiting by the side of the trail, a visceral reminder of the situation. Anyone can climb Mount Kinabalu – it doesn’t require mountaineering skills and can be accomplished in a sturdy pair of walking shoes. The climb is, however, very strenuous and without a moderate level of physical fitness you will suffer. And there’s the unpredictability of altitude sickness –even the strongest of athletes can be hobbled by elevation.

I was aware of the altitude, and decided to take my time. If it took five hours to hike 2.7 kilometers, so be it. As I trudged up the mountain, my progress slowing as I gained more elevation, I thought of every National Geographic special I’d seen about Everest, recalling how climbers would take one step, then rest, another step and another rest. And here I was crossing 12,000 feet, taking a few steps at a time, and resting. I was walking slow, slower than I’d ever walked in my life, slower than a tourist on Seventh Avenue or rush hour traffic on Santa Monica Boulevard.

I pushed on, following the thick white rope that guides climbers up the naked rock to the summit. The full moon had passed a night or two earlier, and I was able to turn off my headlamp and hike by moonlight. Jagged peaks were outlined against the starry sky. Perhaps it was the exhaustion, or the realization that willpower was propelling me closer and closer to my goal. Perhaps it was the elevation. Whatever it was, I couldn’t think about reaching the top without experiencing an upswell of emotion, tears of joy threatening to erupt at any moment. But I kept my emotions in check and set my sights on the only thing that mattered: the summit.

My legs felt great, but I was acutely aware of my lungs and my heart rate. Passing 13,000 feet, I’d push myself 10 or 20 feet and have to stop, gasp for a few breaths while my heart thudded in my chest. It took me an hour to cover the last 500 meters. I covered the final 100 meters at a slow crawl, using hands and feet to clear the jumble of boulders below the summit.

Meanwhile, Julius was like a kid at the playground, jogging up and down the slope behind me and bouncing up and down for warmth. I should have hated him, but was inspired by his enthusiasm. Even after 14 years and countless ascents, he displayed an impish glee at being at the top of the mountain. I’m sure Julius earns a paltry salary for his efforts; he deserves much, much more.

There’s an old saying that the journey is the reward, not the destination. I reached the summit, asked an older Japanese man to take a few pictures of me and was quickly ready to start climbing down. The sun was about to break the horizon, and there were dozens of climbers clamoring for space on the narrow summit. Also, I felt a sudden surge of nausea and didn’t want to vomit on the expanse of Southeast Asia that lay below me.

With the rising sun illuminating the slopes, I took my time on the descent, photographing the peaks that were only outlines an hour before. A cottony layer of cloud covered the land, perhaps a thousand feet below me. I realized that no birds were singing, no frogs croaking, that plant life was stunted and wispy, clinging to the crevices in the rock. I was tired, so tired, but still in awe of the scenery, appreciating every moment I had earned with hard work and perseverance. I was reminded of my love for the Australian Outback and the American Southwest, for the harsh spaces where only the hardiest of species survive. Beaches and forests are great, but for me there’s real beauty in the barren. I wonder where that comes from?

Two hours later I was back at Laban Rata, eating a breakfast of ramen noodles and ready to complete this adventure. But Kinabalu National Park had one more surprise in store for me. The park is in a rainforest. I had been lucky the previous day and climbed without encountering one raindrop. On the descent, however, the rain never let up. It never poured, just a steady mist and drizzle that increased the difficulty of the trek. All those steep slopes, the rocks and roots were now wet and slippery.

On the hike down, we encountered the next day’s climbers making the ascent. I urged them on with words of encouragement, telling them the summit was worth the effort. Around kilometer two an elderly Australian man asked me if the climb got any easier. I should have said it was a piece of cake, but told him the truth, that no, it really doesn’t get any easier, that it’s a slog from start to finish, both going up and coming down. He seemed put off by my answer, but asked me if I’d do it again. Without hesitation, I said “Yes.”

I surprised myself with this quick response. Mount Kinabalu was the toughest climb of my life, a challenge for mind, body and spirit. I loved every terrible minute.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home