On the Road in WA

Having spent a week in Perth I was ready to get on the road again. This time, I’d signed up with a company called Western Xposure for a nine-day trip up the west coast, with stops at two places on the beach and a few days in stunning Karijini National Park. The bus picked me up from my hostel at 7 a.m., then stopped at the bus station to load the rest of the passengers. A diverse group included two Americans, me and Tim, a beer-brewing resident of a remote Alaskan island; one Canadian; four Japanese, including Rina, a who was in Australia to improve her English; a Brazilian; and the usual assortment of Europeans, favorite, Liz from England, the Dutch friends Annick and Juliet, and characters from Italy, Portugal and Germany. Ages ranged from 20 to 54, and as we got to know each other it felt like the mix of personalities would bode well for a fun trip.

Our driver/guide was Dan, from Perth, whose interests are limited to the outdoors and chasing women. He briefs us on the trip and then says there is some bad news. A few days before, a cyclone roared through the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Winds up to 275 kilometers an hour caused extensive damage and a few people were killed. It is front-page news in WA. Dan tells us Karijini is closed to all traffic as the situation is sorted out. If we cannot make it through to Broome, we will be forced to turn around and head back to Perth. I fret for a few minutes then decide to worry about it in a few days. We will make it to Broome, but the cyclone will affect the trip in a big way.

Perth to Kalbarri (March 10, 2007)

Western Australia is the country’s largest state, with about 2 million people. About 73 percent live in Perth, in the southwest. In the country as a whole, there is an average of 2.7 people per square kilometer. In Western Australia, that figure drops to less than 1.

Having traveled more than 7,000 kilometers over land from Sydney to Perth, I appreciate that the country is both vast and empty. Any trip from one place to another covers large stretches of unremarkable scrub and open sky. Miles and miles of highway offer little more than a steady view of flat, open country.

When there is something the break up the landscape (and the monotony), it is most often an unusual natural phenomenon. The Pinnacles in Nambung National Park, 245 kilometers north of Perth, is one natural wonder, and the first stop on the tour.

The park is on the Swan Coastal Plain, an area of shifting yellow sands and coastal heathlands. Out of the yellow sand rise thousand of limestone pillars, a handful more than ten feet tall but most just stumps. Taken alone, each pillar is forgettable. As part of a larger landscape, the Pinnacles are otherworldly, another enigma to marvel over.

The pillars were formed millions of years ago when seashells broke down and were carried inland by the wind. They compacted into limestone and over the years were covered by sand. The dunes stabilized when vegetation took hold, leading to a layer of acidic soil developing over the soft sand below. Over time a hard layer of calcrete formed over the limestone. When plant roots cracked through the calcrete layer, water seeped into the earth and eroded the limestone. What remains today are those areas of limestone that were resistant to erosion (however, they are still eroding today – nothing lasts forever). When winds carried the dunes away, the limestone pillars were exposed.

The Pinnacles reminded me of a site in the Southwest of the United States called Goblin Valley, where toadstool sandstone formations rise from the desert floor. The site was used to excellent effect in the sci-fi farce “Galaxy Quest.”

After the Pinnacles it was a short drive to a series of white sand dunes for some sandboarding. It’s like snowboarding, only slower and you can’t turn. The instructions were to point the board down the dune and hope you don’t fall. The lesson of sandboarding: you are guaranteed to end up with sand in every crevice of your body. Laughing with your fellow travelers as others wipe out at the bottom of the dune is also a great way for the group to get to know one another.

Kalbarri to Monkey Mia (March 11, 2007)

Murchison Gorge in Kalbarri National Park is a preview of what’s to come later in Karijini National Park, a few thousand kilometers north. A river cuts through deep red sandstone to create a scenic gorge. A short hike brings us to a sheer 25-meter cliff, where I take the opportunity to abseil (when did rappelling become abseiling?). I make two trips, first like a normal person with my legs below me, then a gut-busting abseil face down the cliff. I was the first to take the plunge headfirst and am happy to receive a round of applause at the bottom.

A long afternoon of driving and we arrive at Shark Bay, one of 14 World Heritage sites in Australia. The area consists of two small peninsulas that jut into the Indian Ocean. One of these, Peron Peninsula, is the site of Project Eden, a government-sponsored effort to reestablish native wildlife into the peninsula. To do this requires ridding the area of all introduced species – cats, rabbits foxes, goats – and reintroducing native species. To keep the feral beasts out of the area, the government has erected a vermin fence spanning the 4-kilometer entrance to the peninsula. There is a road that the fence cannot cross, but there is a unique solution. Any creature that comes near the fence is greeted by a recording of barking dogs and truck horns.

Shark Bay also features a natural wonder that is one of the reasons I came to Western Australia. I learned about stromatolites when I read Bill Bryson’s travelogue about Australia, which is called “Down Under” in the U.K. and Australia and "In a Sunburned Country" in the U.S. The single-celled creatures were the first living organisms to emerge on the planet. Stromatolite fossils have been dated to 4.5 billion years ago, and were the only form of life on the planet for nearly 2 billion years. They gave rise to other single-celled creatures, then multi-celled organisms. The rest is biological history. They are a testament to evolution and, amazingly, there are a few colonies that survive today.

However, stromatolites are not much to look at, merely black rocks in a tidal pool. But with a little backstory, they are fascinating. At least I thought so. Others in the group seemed ready to go after a few minutes.

Monkey Mia to Exmouth (March 12-14, 2007)

The coastal resorts of Monkey Mia and Coral Bay and the town of Exmouth are the main attractions in this part of Western Australia.

Monkey Mia is a resort village best known for the dolphins that show up like clockwork every morning. Tourists gather on the shore for the show, receiving an instructional brief from a park ranger before taking part in a short feeding. The dolphins are wild and must fend for themselves the rest of the day. I think dolphins are interesting, and there was a calf in the group that made an appearance, but the spectacle of a hundred tourists gathered on the shore strikes me as easy entertainment for the masses. If I’d never seen a dolphin before I might have been entertained.

Also depressing was a stop at Ocean Park, a ramshackle, privately owned “aquarium” with a handful of small pools holding sharks and rays and tanks containing sea snakes, turtles and a few poisonous specimens. Ocean Park operates as both a marine rehabilitation facility and a tourist attraction. I don’t know how well they are doing as a rehabilitation facility; as a tourist attraction it was dismal. I was reminded of unscheduled stops in third world countries in which you can witness children making carpets. Nevertheless, seeing a deadly stone fish (you die from the pain, not the poison) and touching a sea snake was worth the $5 price of admission.

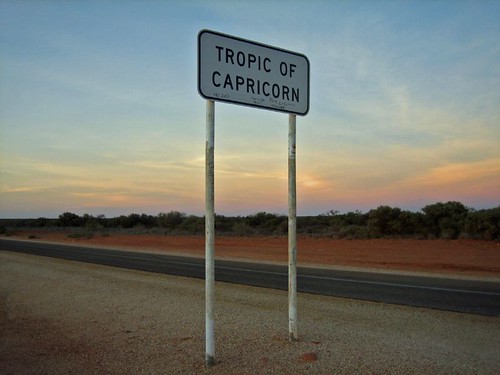

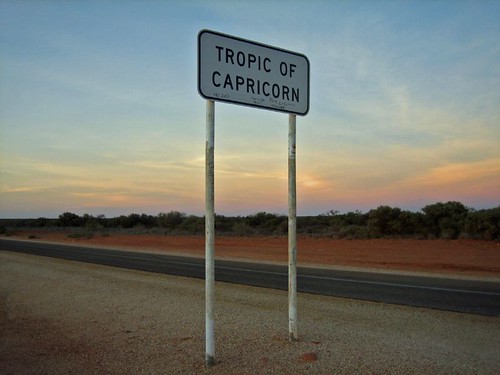

More than 400 kilometers north is Coral Bay. About 50 kilometers from the town, the highway crosses the Tropic of Capricorn. There is a sign and a white line painted on the road. After taking photos, we took turns writing our names on the line with a fat magic marker. I was not amused by Ocean Park, yet the stony stromatolites and a geographical marker in the middle of nowhere gave me great pleasure. What does that say about me? Comments?

Coral Bay is bigger than Monkey Mia. When I say bigger, understand that the population is only about 150. But Coral Bay is a gateway to the Ningaloo Reef, the largest west-coast reef in the world.

One of Australia’s most famous attractions if the Great Barrier Reef, on the east coast in Queensland. I’ve been told that Ningaloo Reef, which is protected within Ningaloo Marine Park, rivals the Great Barrier, but unlike the Great Barrier, which requires visitors to travel by boat to get to the reef, it’s only about 100 meters from the beach. Another big plus for Ningaloo is that it gets a small fraction of Great Barrier’s traffic.

On the morning of March 13, I sign up for a three-hour kayak/snorkeling tour. It’s a short paddle to a spot where sharks gather to clean their gills. Another short paddle takes us to a spot featuring the usual assortment of colorful coral and fish and we see a couple of sea turtles. The water is not as clear as it could be because the night before, the coral spawned. This annual event happens after the full moon in March, when the coral release sperm and eggs into the water. Best not to think about what you are swimming through.

The trip from Perth has included a few days of solid driving, and after kayaking it’s a relief to spend the rest of the afternoon lounging at the beach. The water is warm, the sand is white and the beach is beautiful. It seems like we spend more time floating in the shallows than sitting on the beach, playing like children on a summer’s day.

Another 200 kilometers north is the town of Exmouth (pronounced like it is spelled: Ex-Mouth), population 2,500. It is the base for the northern end of the Ningaloo Reef. Sixty kilometers further is Turquoise Bay, one of the best beaches I’ve been to in my life, maybe the best. If Coral Bay was beautiful, Turquoise Bay is exquisite. It’s hard to believe from the perfect conditions that a cyclone roared through the area a week before.

Turquoise Bay is the kind of place I came halfway across the world to experience: remote, relaxing, and extraordinarily beautiful with fun activities and very few people. It’s the kind of place that justifies all the planning, travel, time and money. Of all the beaches I’ve seen in Australia, Turquoise Bay is the one I want to return to the most.

After setting up shelter, about 15 of us gather for a drift snorkel. We walk down the beach, around a point and along a few hundred meters of the reef. There are strong currents and rip tides at Turquoise Bay, strong enough to sweep lazy or weak swimmers out to sea, permanently. And Dan makes sure we know if, saying, “If you don’t make it back to shore, you will be swept out there, and I won’t come after you.”

But if you exit the water before reaching the rip, there’s no problem. And since the current along the reef is so strong, you can let the water carry you over the reef, expending little energy other than pointing and oohing and aahing at the marine life below. On the first trip over the reef, as a group, there are no reef sharks or turtles. Later, in the afternoon, I go out again with a small group at high tide. We enter the water and bang, there’s a 4-foot black-tipped reef shark about ten feet in front of me.

The reef shark looks for an escape, gliding quickly left and right before darting off into the murk. But a minute later there’s another one. Or is it the same shark? Same coloration, same size. It swims away. Then a minute later there’s another. This time I’m convinced it’s one shark circling the area looking for food.

Since seeing “Jaws” as a child I’ve harbored an irrational fear of sharks. I previously wrote about swimming with dolphins in Victoria, where a “shark shield” was offered as protection against predators. While snorkeling in Coral Bay and today, there are no man-eaters, but I’m still nervous about swimming in open water with sharks. Once I see them up close, I realize most really are more afraid of me than I am of them. .

Karijini National Park (March 15-17, 2007)

We learn while in Exmouth that the roads to Broome are open and that Karijini National Park is scheduled to reopen by the time we arrive in the evening of March 15. We also learn that because of the cyclone, the tour that left before us was unable to continue to Broome and that there is no bus to take passengers back to Perth. This doesn’t affect me because I’m flying out of Broome, but causes some anxiety for others on the tour.

After all the complaining I did about being stuck in Perth, it ends up benefiting me. If I had joined the tour five days earlier I would not have been able to experience Karijini.

Saying goodbye to Ningaloo Reef, we are on the road most of the day, arriving at Karijini National Park in the late afternoon. The cyclone has fed the landscape, and the park is a riot of deep red rock and bright green scrub. After all the gray, green and white scrub on the coast, the colors are a magnificent treat. I can tell I am going to like this place and I’m haven't gotten off the bus yet.

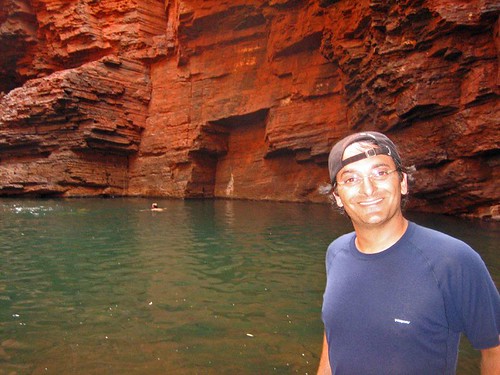

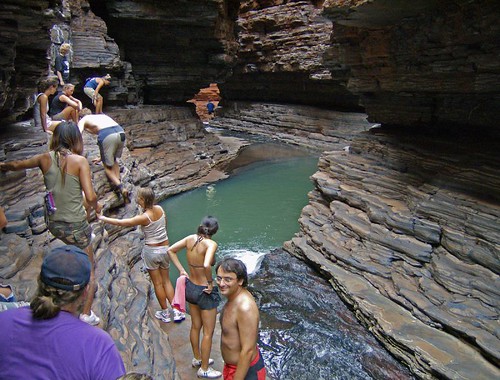

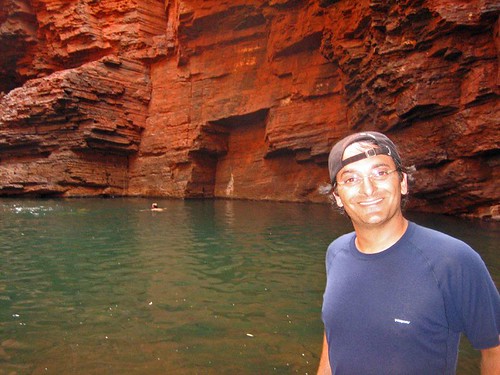

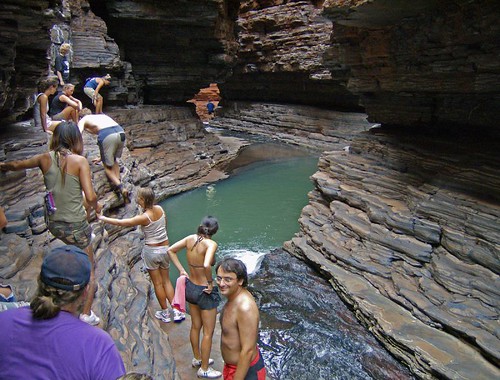

When I booked the tour in Perth, my travel agent described Karijini as “Australia’s Best Kept Secret.” Our guide describes it the same way. I had also seen Karijini profiled in a few travel shows. The love comes from a series of gorges offering the chance to do a bit of canyoneering, a general term a mix of walking, swimming, rock climbing and abseiling through narrow canyons. The most famous hike, called Miracle Mile, is no longer open due to safety concerns, but we are told that we will enter a few of the gorges, some of them no more than 3 or 4 feet wide and a few hundred feet deep, for a taste of adventure.

Up to this point we’ve been sleeping in backpackers’ hostels. Tonight I will finally get the chance to sleep in a swag, which is basically a canvas bedroll with a mattress built in. You roll it out on the ground, put your sleeping bag inside, and sleep under the stars. I had not heard of a swag before arriving in Australia and was very excited about the night ahead.

Not everyone shared my enthusiasm and most spent the night crowded on a huge tarp next to the bus. I chose a spot about 100 feet away, as did three other campers. At about 3 in the morning, I was woken by a scream and saw Julie, a woman from France with little interest in camping, run by my swag. “There was a dog right next to me,” she shrieked. Then she blinded me with her flashlight and begged to know if it was really a dog and whether it was dangerous. I told her it was probably a dingo and that it would not eat her unless she was a kangaroo. Dingo sightings are rare, and the only person who saw it was the one least interested in the outdoors. Unfair. At least I got to see the poisonous red-backed spider that lives in the outhouse.

In Karijini over the next two days, we swam in freshwater pools, bathed under waterfalls, squeezed through narrow gorges and traversed rock walls above stony riverbeds. The gorges are imposing and the hiking treacherous. There are many fascinating geological specimens (rocks), including the oldest exposed rock on the planet (about 4.5 billion years old). There was only one minor injury (Marcus, from Germany, twisted his ankle on the first hike) and no one died, even though slipping and falling from any number of places would have resulted sever injury and possible death. When you are 30 feet above a canyon floor, inching along a narrow ledge, you can only think about not falling. I agree with the sentiment that Karijini is Australia’s best-kept secret. It is spectacular. When and how can I return?

One hike worth mentioning was on the morning of our first full day. We walked down a path to Fern Pool, a secluded waterhole with a pair of small waterfalls. After a short swim, we continued down to Fortescue Falls, where a small a trickle washed down the slanted rock. Further down the gorge, there was debris from the runoff after the cyclone, knotted trees and branches and flattened grass. As we approached a side channel to visit a place called Circular Pool, it started to rain, not hard, but enough to get us wet. We continued to the pool and the rain got heavier. A very quick look and we turned around and started hiking up a side trail back to the bus. As we ascended, the rain increased. By the time we reached the top, it was an absolute downpour.

I’m not keen on walking in the rain, but this was an exhilarating experience. In just a few minutes, dry canyon became line with waterfalls. The riverbed we had walked down was visibly higher and would have been impossible to walk along. The landscape changed within an hour from fairly dry to spectacularly wet. We returned by bus to Fortescue Falls, and what had been a trickle was now a torrent. The trail we had taken was completely underwater. I’ll take a soaking in Karijini any day.

Karijini to Broome (March 17-18, 2007)

Not everything goes according to plan on tour. We leave Karijini in the afternoon and set out for a sheep station where we will camp for the night. We will still be sleeping in swags, but we are promised hot showers and flush toilets. The stench in the bus tells me showers are an excellent idea for everyone.

We arrive at the sheep station, a 500,000 square kilometer private farm where there are camping facilities for tourists. We turn off the road and onto a dirt road, where Dan tells the group that we are crossing a dry river bed that becomes impassable maybe one a year when it floods. After about 200 meters, the bus gets bogged in deep sand and we are told to get out and push. No kidding. And we don’t even have to pay extra for the experience. We spend the next 30 minutes digging and pushing to free the bus. We make it across the dry river bed as the sun sets only to travel another 100 meters to discover a wide torrent of water blocking the road. It seems we’ve arrived at the rare time when the river is flowing.

The water is runoff from the cyclone the previous week. There is a truck on the other side of the river, about 100 meters away, and Dan sets off into the river armed with a shovel to test the depth and for stability. The water is never higher than his thigh, but still too high and fast for us to cross in the bus. And we learn when he returns that the cyclone has flattened all the facilities. The farmhouse is standing, but the campground and showers have been destroyed. There’s nothing for us to do but turn around and look for someplace to spend the night. We give ourselves a round of applause for making it out of the sheep station after two rough hours in the dark.

We head up the dark highway for 35 kilometers to a parking area that is nothing more than tarmac and a yellow rubbish bin. We pull in at about 10 p.m., park the bus and prepare dinner. There is nothing but the bus, we campers, tarmac, scrub, the occasional road train on the highway and a billion crickets, mosquitoes (mozzies) and other insects.

It is out last night of the tour and we’ve become a functional group, so we make the most of the situation, preparing dinner and drinking the last of the beer. When a brief spot of rain comes, we take shelter in the sweltering bus. But it passes and we continue our roadside party. There had been two birthdays during the tour and someone pulls out candles and sparklers. Desert, beer, fatigue and sparklers – who needs drugs for a surreal experience?

Bedtime approaches and we lay out our swags in line with the bus, just in case a road train stops during the night. There are still dark clouds in the sky and it looks like there will be no escape from the rain.

I sleep until about 3 a.m., when I feel drops on my face. The scattered drops intensify into a steady rain as people scramble for shelter in the bus. I’m too tired to move so I zip up my swag and cover my head as best I can. It’s too late though, and half of the inside of the swag is soaked with rainwater. Swags are also pretty hot and the enclosed space starts me sweating. Within a few minutes I’m a damp camper. I tough it out and somehow fall back to sleep.

When I wake up before sunrise, only 5 of the 19 campers are outside. The rest have suffered through sauna-like conditions in the bus, getting little to no sleep. Staying out in the run and sleeping in a puddle turns out to be the right choice.

It was a miserable experience, but somehow I’m not too perturbed and wake up fatigued but happy. It’s not the worst night I’ve spent camping. As the sun rises, a perfect rainbow forms to the west, delivering an ironic message I have yet to decipher.

The rest of the day is an exhausting slog over 700 kilometers of empty landscape.

We stop a roadhouse for showers then at another for lunch, but the day is consumed with a the push towards Broome. We arrive in the early evening, exchange hugs and email addresses, and say farewell to a memorable tour.

There is a lot more I could say about this trip. There are logistics and personalities, the monotony of the food and the minutiae of traveling as a group. I hope to get into it all in the near future. In the meantime, if you have any questions or comments, anything you’d like me to write about on Packmonkey, drop me a line.

Flickr Photo Set: Western Australia (206 Photos)

Our driver/guide was Dan, from Perth, whose interests are limited to the outdoors and chasing women. He briefs us on the trip and then says there is some bad news. A few days before, a cyclone roared through the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Winds up to 275 kilometers an hour caused extensive damage and a few people were killed. It is front-page news in WA. Dan tells us Karijini is closed to all traffic as the situation is sorted out. If we cannot make it through to Broome, we will be forced to turn around and head back to Perth. I fret for a few minutes then decide to worry about it in a few days. We will make it to Broome, but the cyclone will affect the trip in a big way.

Perth to Kalbarri (March 10, 2007)

Western Australia is the country’s largest state, with about 2 million people. About 73 percent live in Perth, in the southwest. In the country as a whole, there is an average of 2.7 people per square kilometer. In Western Australia, that figure drops to less than 1.

Having traveled more than 7,000 kilometers over land from Sydney to Perth, I appreciate that the country is both vast and empty. Any trip from one place to another covers large stretches of unremarkable scrub and open sky. Miles and miles of highway offer little more than a steady view of flat, open country.

When there is something the break up the landscape (and the monotony), it is most often an unusual natural phenomenon. The Pinnacles in Nambung National Park, 245 kilometers north of Perth, is one natural wonder, and the first stop on the tour.

The park is on the Swan Coastal Plain, an area of shifting yellow sands and coastal heathlands. Out of the yellow sand rise thousand of limestone pillars, a handful more than ten feet tall but most just stumps. Taken alone, each pillar is forgettable. As part of a larger landscape, the Pinnacles are otherworldly, another enigma to marvel over.

The pillars were formed millions of years ago when seashells broke down and were carried inland by the wind. They compacted into limestone and over the years were covered by sand. The dunes stabilized when vegetation took hold, leading to a layer of acidic soil developing over the soft sand below. Over time a hard layer of calcrete formed over the limestone. When plant roots cracked through the calcrete layer, water seeped into the earth and eroded the limestone. What remains today are those areas of limestone that were resistant to erosion (however, they are still eroding today – nothing lasts forever). When winds carried the dunes away, the limestone pillars were exposed.

The Pinnacles reminded me of a site in the Southwest of the United States called Goblin Valley, where toadstool sandstone formations rise from the desert floor. The site was used to excellent effect in the sci-fi farce “Galaxy Quest.”

After the Pinnacles it was a short drive to a series of white sand dunes for some sandboarding. It’s like snowboarding, only slower and you can’t turn. The instructions were to point the board down the dune and hope you don’t fall. The lesson of sandboarding: you are guaranteed to end up with sand in every crevice of your body. Laughing with your fellow travelers as others wipe out at the bottom of the dune is also a great way for the group to get to know one another.

Kalbarri to Monkey Mia (March 11, 2007)

Murchison Gorge in Kalbarri National Park is a preview of what’s to come later in Karijini National Park, a few thousand kilometers north. A river cuts through deep red sandstone to create a scenic gorge. A short hike brings us to a sheer 25-meter cliff, where I take the opportunity to abseil (when did rappelling become abseiling?). I make two trips, first like a normal person with my legs below me, then a gut-busting abseil face down the cliff. I was the first to take the plunge headfirst and am happy to receive a round of applause at the bottom.

A long afternoon of driving and we arrive at Shark Bay, one of 14 World Heritage sites in Australia. The area consists of two small peninsulas that jut into the Indian Ocean. One of these, Peron Peninsula, is the site of Project Eden, a government-sponsored effort to reestablish native wildlife into the peninsula. To do this requires ridding the area of all introduced species – cats, rabbits foxes, goats – and reintroducing native species. To keep the feral beasts out of the area, the government has erected a vermin fence spanning the 4-kilometer entrance to the peninsula. There is a road that the fence cannot cross, but there is a unique solution. Any creature that comes near the fence is greeted by a recording of barking dogs and truck horns.

Shark Bay also features a natural wonder that is one of the reasons I came to Western Australia. I learned about stromatolites when I read Bill Bryson’s travelogue about Australia, which is called “Down Under” in the U.K. and Australia and "In a Sunburned Country" in the U.S. The single-celled creatures were the first living organisms to emerge on the planet. Stromatolite fossils have been dated to 4.5 billion years ago, and were the only form of life on the planet for nearly 2 billion years. They gave rise to other single-celled creatures, then multi-celled organisms. The rest is biological history. They are a testament to evolution and, amazingly, there are a few colonies that survive today.

However, stromatolites are not much to look at, merely black rocks in a tidal pool. But with a little backstory, they are fascinating. At least I thought so. Others in the group seemed ready to go after a few minutes.

Monkey Mia to Exmouth (March 12-14, 2007)

The coastal resorts of Monkey Mia and Coral Bay and the town of Exmouth are the main attractions in this part of Western Australia.

Monkey Mia is a resort village best known for the dolphins that show up like clockwork every morning. Tourists gather on the shore for the show, receiving an instructional brief from a park ranger before taking part in a short feeding. The dolphins are wild and must fend for themselves the rest of the day. I think dolphins are interesting, and there was a calf in the group that made an appearance, but the spectacle of a hundred tourists gathered on the shore strikes me as easy entertainment for the masses. If I’d never seen a dolphin before I might have been entertained.

Also depressing was a stop at Ocean Park, a ramshackle, privately owned “aquarium” with a handful of small pools holding sharks and rays and tanks containing sea snakes, turtles and a few poisonous specimens. Ocean Park operates as both a marine rehabilitation facility and a tourist attraction. I don’t know how well they are doing as a rehabilitation facility; as a tourist attraction it was dismal. I was reminded of unscheduled stops in third world countries in which you can witness children making carpets. Nevertheless, seeing a deadly stone fish (you die from the pain, not the poison) and touching a sea snake was worth the $5 price of admission.

More than 400 kilometers north is Coral Bay. About 50 kilometers from the town, the highway crosses the Tropic of Capricorn. There is a sign and a white line painted on the road. After taking photos, we took turns writing our names on the line with a fat magic marker. I was not amused by Ocean Park, yet the stony stromatolites and a geographical marker in the middle of nowhere gave me great pleasure. What does that say about me? Comments?

Coral Bay is bigger than Monkey Mia. When I say bigger, understand that the population is only about 150. But Coral Bay is a gateway to the Ningaloo Reef, the largest west-coast reef in the world.

One of Australia’s most famous attractions if the Great Barrier Reef, on the east coast in Queensland. I’ve been told that Ningaloo Reef, which is protected within Ningaloo Marine Park, rivals the Great Barrier, but unlike the Great Barrier, which requires visitors to travel by boat to get to the reef, it’s only about 100 meters from the beach. Another big plus for Ningaloo is that it gets a small fraction of Great Barrier’s traffic.

On the morning of March 13, I sign up for a three-hour kayak/snorkeling tour. It’s a short paddle to a spot where sharks gather to clean their gills. Another short paddle takes us to a spot featuring the usual assortment of colorful coral and fish and we see a couple of sea turtles. The water is not as clear as it could be because the night before, the coral spawned. This annual event happens after the full moon in March, when the coral release sperm and eggs into the water. Best not to think about what you are swimming through.

The trip from Perth has included a few days of solid driving, and after kayaking it’s a relief to spend the rest of the afternoon lounging at the beach. The water is warm, the sand is white and the beach is beautiful. It seems like we spend more time floating in the shallows than sitting on the beach, playing like children on a summer’s day.

Another 200 kilometers north is the town of Exmouth (pronounced like it is spelled: Ex-Mouth), population 2,500. It is the base for the northern end of the Ningaloo Reef. Sixty kilometers further is Turquoise Bay, one of the best beaches I’ve been to in my life, maybe the best. If Coral Bay was beautiful, Turquoise Bay is exquisite. It’s hard to believe from the perfect conditions that a cyclone roared through the area a week before.

Turquoise Bay is the kind of place I came halfway across the world to experience: remote, relaxing, and extraordinarily beautiful with fun activities and very few people. It’s the kind of place that justifies all the planning, travel, time and money. Of all the beaches I’ve seen in Australia, Turquoise Bay is the one I want to return to the most.

After setting up shelter, about 15 of us gather for a drift snorkel. We walk down the beach, around a point and along a few hundred meters of the reef. There are strong currents and rip tides at Turquoise Bay, strong enough to sweep lazy or weak swimmers out to sea, permanently. And Dan makes sure we know if, saying, “If you don’t make it back to shore, you will be swept out there, and I won’t come after you.”

But if you exit the water before reaching the rip, there’s no problem. And since the current along the reef is so strong, you can let the water carry you over the reef, expending little energy other than pointing and oohing and aahing at the marine life below. On the first trip over the reef, as a group, there are no reef sharks or turtles. Later, in the afternoon, I go out again with a small group at high tide. We enter the water and bang, there’s a 4-foot black-tipped reef shark about ten feet in front of me.

The reef shark looks for an escape, gliding quickly left and right before darting off into the murk. But a minute later there’s another one. Or is it the same shark? Same coloration, same size. It swims away. Then a minute later there’s another. This time I’m convinced it’s one shark circling the area looking for food.

Since seeing “Jaws” as a child I’ve harbored an irrational fear of sharks. I previously wrote about swimming with dolphins in Victoria, where a “shark shield” was offered as protection against predators. While snorkeling in Coral Bay and today, there are no man-eaters, but I’m still nervous about swimming in open water with sharks. Once I see them up close, I realize most really are more afraid of me than I am of them. .

Karijini National Park (March 15-17, 2007)

We learn while in Exmouth that the roads to Broome are open and that Karijini National Park is scheduled to reopen by the time we arrive in the evening of March 15. We also learn that because of the cyclone, the tour that left before us was unable to continue to Broome and that there is no bus to take passengers back to Perth. This doesn’t affect me because I’m flying out of Broome, but causes some anxiety for others on the tour.

After all the complaining I did about being stuck in Perth, it ends up benefiting me. If I had joined the tour five days earlier I would not have been able to experience Karijini.

Saying goodbye to Ningaloo Reef, we are on the road most of the day, arriving at Karijini National Park in the late afternoon. The cyclone has fed the landscape, and the park is a riot of deep red rock and bright green scrub. After all the gray, green and white scrub on the coast, the colors are a magnificent treat. I can tell I am going to like this place and I’m haven't gotten off the bus yet.

When I booked the tour in Perth, my travel agent described Karijini as “Australia’s Best Kept Secret.” Our guide describes it the same way. I had also seen Karijini profiled in a few travel shows. The love comes from a series of gorges offering the chance to do a bit of canyoneering, a general term a mix of walking, swimming, rock climbing and abseiling through narrow canyons. The most famous hike, called Miracle Mile, is no longer open due to safety concerns, but we are told that we will enter a few of the gorges, some of them no more than 3 or 4 feet wide and a few hundred feet deep, for a taste of adventure.

Up to this point we’ve been sleeping in backpackers’ hostels. Tonight I will finally get the chance to sleep in a swag, which is basically a canvas bedroll with a mattress built in. You roll it out on the ground, put your sleeping bag inside, and sleep under the stars. I had not heard of a swag before arriving in Australia and was very excited about the night ahead.

Not everyone shared my enthusiasm and most spent the night crowded on a huge tarp next to the bus. I chose a spot about 100 feet away, as did three other campers. At about 3 in the morning, I was woken by a scream and saw Julie, a woman from France with little interest in camping, run by my swag. “There was a dog right next to me,” she shrieked. Then she blinded me with her flashlight and begged to know if it was really a dog and whether it was dangerous. I told her it was probably a dingo and that it would not eat her unless she was a kangaroo. Dingo sightings are rare, and the only person who saw it was the one least interested in the outdoors. Unfair. At least I got to see the poisonous red-backed spider that lives in the outhouse.

In Karijini over the next two days, we swam in freshwater pools, bathed under waterfalls, squeezed through narrow gorges and traversed rock walls above stony riverbeds. The gorges are imposing and the hiking treacherous. There are many fascinating geological specimens (rocks), including the oldest exposed rock on the planet (about 4.5 billion years old). There was only one minor injury (Marcus, from Germany, twisted his ankle on the first hike) and no one died, even though slipping and falling from any number of places would have resulted sever injury and possible death. When you are 30 feet above a canyon floor, inching along a narrow ledge, you can only think about not falling. I agree with the sentiment that Karijini is Australia’s best-kept secret. It is spectacular. When and how can I return?

One hike worth mentioning was on the morning of our first full day. We walked down a path to Fern Pool, a secluded waterhole with a pair of small waterfalls. After a short swim, we continued down to Fortescue Falls, where a small a trickle washed down the slanted rock. Further down the gorge, there was debris from the runoff after the cyclone, knotted trees and branches and flattened grass. As we approached a side channel to visit a place called Circular Pool, it started to rain, not hard, but enough to get us wet. We continued to the pool and the rain got heavier. A very quick look and we turned around and started hiking up a side trail back to the bus. As we ascended, the rain increased. By the time we reached the top, it was an absolute downpour.

I’m not keen on walking in the rain, but this was an exhilarating experience. In just a few minutes, dry canyon became line with waterfalls. The riverbed we had walked down was visibly higher and would have been impossible to walk along. The landscape changed within an hour from fairly dry to spectacularly wet. We returned by bus to Fortescue Falls, and what had been a trickle was now a torrent. The trail we had taken was completely underwater. I’ll take a soaking in Karijini any day.

Karijini to Broome (March 17-18, 2007)

Not everything goes according to plan on tour. We leave Karijini in the afternoon and set out for a sheep station where we will camp for the night. We will still be sleeping in swags, but we are promised hot showers and flush toilets. The stench in the bus tells me showers are an excellent idea for everyone.

We arrive at the sheep station, a 500,000 square kilometer private farm where there are camping facilities for tourists. We turn off the road and onto a dirt road, where Dan tells the group that we are crossing a dry river bed that becomes impassable maybe one a year when it floods. After about 200 meters, the bus gets bogged in deep sand and we are told to get out and push. No kidding. And we don’t even have to pay extra for the experience. We spend the next 30 minutes digging and pushing to free the bus. We make it across the dry river bed as the sun sets only to travel another 100 meters to discover a wide torrent of water blocking the road. It seems we’ve arrived at the rare time when the river is flowing.

The water is runoff from the cyclone the previous week. There is a truck on the other side of the river, about 100 meters away, and Dan sets off into the river armed with a shovel to test the depth and for stability. The water is never higher than his thigh, but still too high and fast for us to cross in the bus. And we learn when he returns that the cyclone has flattened all the facilities. The farmhouse is standing, but the campground and showers have been destroyed. There’s nothing for us to do but turn around and look for someplace to spend the night. We give ourselves a round of applause for making it out of the sheep station after two rough hours in the dark.

We head up the dark highway for 35 kilometers to a parking area that is nothing more than tarmac and a yellow rubbish bin. We pull in at about 10 p.m., park the bus and prepare dinner. There is nothing but the bus, we campers, tarmac, scrub, the occasional road train on the highway and a billion crickets, mosquitoes (mozzies) and other insects.

It is out last night of the tour and we’ve become a functional group, so we make the most of the situation, preparing dinner and drinking the last of the beer. When a brief spot of rain comes, we take shelter in the sweltering bus. But it passes and we continue our roadside party. There had been two birthdays during the tour and someone pulls out candles and sparklers. Desert, beer, fatigue and sparklers – who needs drugs for a surreal experience?

Bedtime approaches and we lay out our swags in line with the bus, just in case a road train stops during the night. There are still dark clouds in the sky and it looks like there will be no escape from the rain.

I sleep until about 3 a.m., when I feel drops on my face. The scattered drops intensify into a steady rain as people scramble for shelter in the bus. I’m too tired to move so I zip up my swag and cover my head as best I can. It’s too late though, and half of the inside of the swag is soaked with rainwater. Swags are also pretty hot and the enclosed space starts me sweating. Within a few minutes I’m a damp camper. I tough it out and somehow fall back to sleep.

When I wake up before sunrise, only 5 of the 19 campers are outside. The rest have suffered through sauna-like conditions in the bus, getting little to no sleep. Staying out in the run and sleeping in a puddle turns out to be the right choice.

It was a miserable experience, but somehow I’m not too perturbed and wake up fatigued but happy. It’s not the worst night I’ve spent camping. As the sun rises, a perfect rainbow forms to the west, delivering an ironic message I have yet to decipher.

The rest of the day is an exhausting slog over 700 kilometers of empty landscape.

We stop a roadhouse for showers then at another for lunch, but the day is consumed with a the push towards Broome. We arrive in the early evening, exchange hugs and email addresses, and say farewell to a memorable tour.

There is a lot more I could say about this trip. There are logistics and personalities, the monotony of the food and the minutiae of traveling as a group. I hope to get into it all in the near future. In the meantime, if you have any questions or comments, anything you’d like me to write about on Packmonkey, drop me a line.

Flickr Photo Set: Western Australia (206 Photos)

1 Comments:

Amazing photos!! Please don't tell me you Photoshop them in any way (including your tan). I don't know how you'll be able to stand living in a dirty city again.

Post a Comment

<< Home